Cathy’s Work

Click on the titles of work below to view

Publications

The Forest, Alberto Giacometti, 1950 at Metphrastics: an online poetry journal inspired by works in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. (This poem is part of Cathy‘s manuscript, The Music Must Sing Itself: an elegy in ekphrasis [submitted for publication].)

Max Beckman, Still Life With Fallen Candles, oil on canvas, 1929 and Otto Dix, Horse Cadaver, etching and drypoint, 1924 are featured in Fantastic Imaginary Creatures, Madville Press, May 2024.

Amédée Ozenfant, Accords, oil on canvas, 1922 in The Ekphrastic Review. (This poem is part of Cathy‘s manuscript, The Music Must Sing Itself: an elegy in ekphrasis [submitted for publication].)

Genesis 2:20, at page 67 in Book of Matches, September 1, 2023 – bookofmatcheslitmag.com/post/issue-9-s-silky-smooth-release

knotted was an inaugural chapbook contest finalist at Lefty Blondie Press in June 2023.

Four poems in Isele Magazine, April 2023: Fleeting, Researchers Have Engineered-Out the Natural Dispersion of Crop Seeds, A Day So Happy, and Prodigal Garden Pruner

Succulent appeared on Viewless Wings podcast in April 2023.

knotted, a chapbook, was among the top 5 finalists in the Minerva Rising 2022 Dare to Be… chapbook contest

At the Fish Tank in Madrid, Superpresent, Winter 2023 at page 36.

“Out-of-Body”

Cathy’s poem “Out-of-Body” is in the anthology Dionne’s Story: Volume 3, October 2022

Out-of-Body

I keep my eyes open so I can not see.

My viewfinder in nightmares sees

moonlit bodies stumbling in the surf

laughing slapping not seeing her

back slashed pink by scruffy beach.

She screams wide her vocal cords crimped

as if grit of littered boardwalk will rise to protect.

My lips part to assist. Sand hears as well

as any human ear waning pleas for help.

She kicks leaden stumps useless legs like mine

bound in sheets paralyzed unable to shove

bodies off. Hips rise in self-disgust

to bottles some plastic some glass.

Moonlit green is pretty and brutal.

My own hands draw blood in clammy flesh

clawed weapons of self-defense

that cannot protect her face.

My groggy head too heavy to lift.

I open numb lips to the taste of blood

in crescents carved on her face

by scores of jeering teeth.

Each a copycat each a coward hiding

behind eyelids my own.

Work to Do and Sex, Drugs and Alcohol were featured in Rumors Secrets & Lies, Anhinga Press 2022 features

Sisters Twisting Beatitudes, Psaltery and Lyre, September 19, 2022.

Resting At Your Grave, I Remember When You Said, “I Love You, Wittmeyer”, Flash Glass 2022

The Flashglass 2023 anthology is available online or in print at https://www.rowanglassworks.

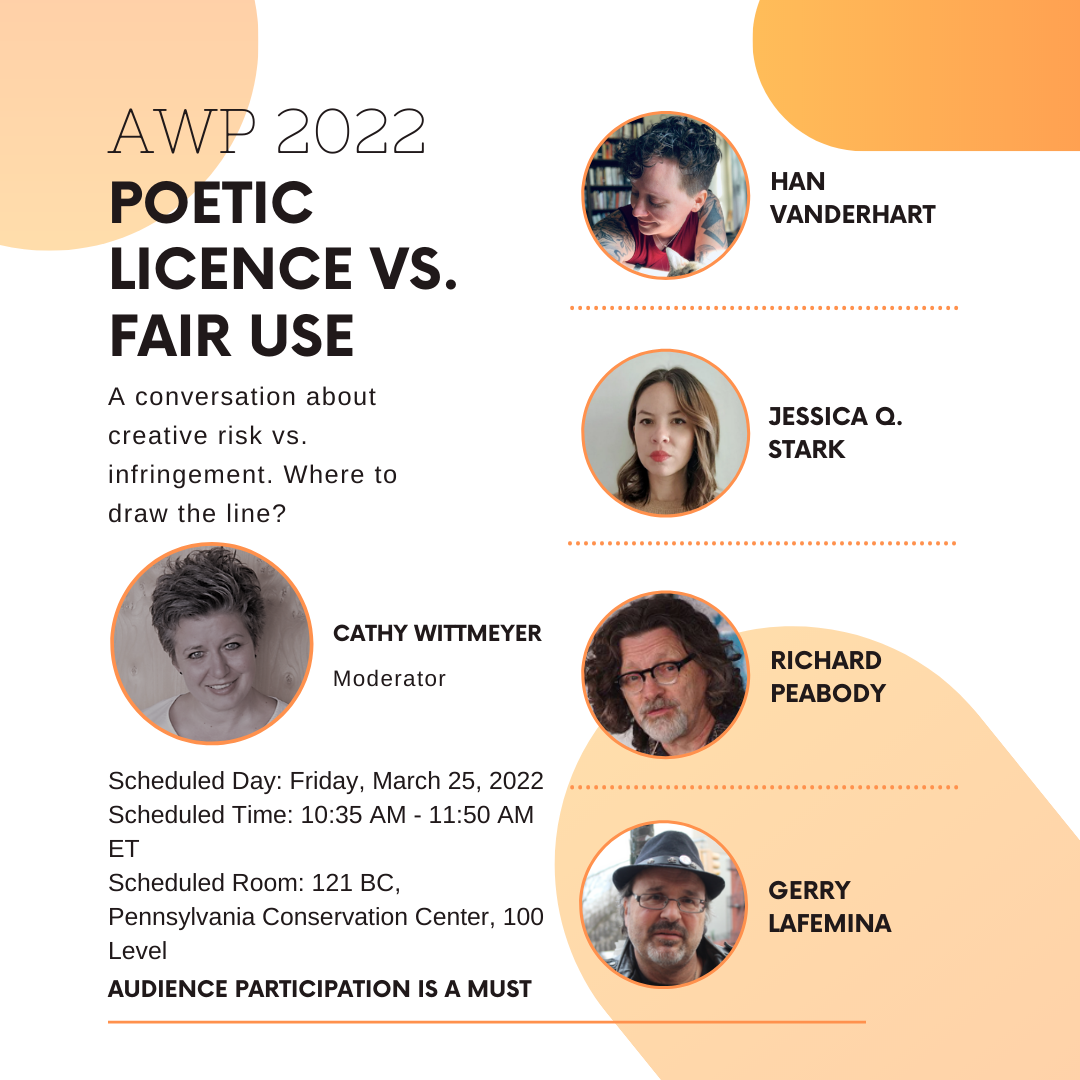

Where Do You Get A Poetic License to Infringe Copyright?

AWP: Writer’s Chronicle Features Archive

Where Do You Get a Poetic License to Infringe Copyright?

Cathy Wittmeyer | February 2022

Cathy Wittmeyer

Poetic license is defined by Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary as, “license, or liberty, taken by a poet, prose writer, or other artist in deviating from rule, conventional form, logic, or fact, in order to produce a desired effect.” The deviated rule this essay investigates is copyright infringement in derivative works. The question was raised by a poet in a Tweet, “Is it okay to use song lyrics in a poem?” and I patiently watched poets comment with all sorts of justifications that were less than legally precise. I propose that it can be perfectly fine to borrow music lyrics for a poem, or a line from another poem without permission. It can also be wrong to do so and poses risks poets and publishers may not want to undertake.

The Copyright Act of 1976 gets its power from the First Amendment, and its intent is to encourage the building upon the ideas of others and the free exchange of ideas by creating incentive to share. It is the expression, not the idea, of the originator that is protected. According to the United States Copyright Office (Circular 14), the owner of a copyright is the only one who has the right to adapt their work or authorize someone else to, but some fair use exceptions do exist. Fair use is a defense against a charge of copyright infringement. There is no reason for a poet to use the fair use defense unless they are being sued. Poets might simply ask what the risk of being sued is before they borrow lines and make their choices based on their level of risk aversion.

The Copyright Act of 1976 gets its power from the First Amendment, and its intent is to encourage the building upon the ideas of others and the free exchange of ideas by creating incentive to share.

As with all legal exceptions, there is a legal test, a set of questions one must ask to determine whether using someone else’s line of lyric is fair use without permission. These have been developed over decades of cases, and a defendent needs to take steps to prove the use was fair: the nature of the work, the significance of the copied content, and the potential impact to the copyright owner’s income and reputation.

A poet who claims poetic license to use someone else’s line or lines without permission, must meet this very subjective test if they are sued for using the material without permission. A poet cannot simply say they meet the test to avoid a legal challenge so must take the first step and consider the nature of the derivative work: is it newsworthy, parody or comedy, and therefore, transformative art? If it is a poem, it is probably art, and not reportage or parody. If, however, it is paying homage to a great poet and also creating something new in tribute, we could have a case for fair use in the first step, and could then move on to the second and third steps.

Take for example, a poem with the title, “Wind” that has the epigraph, after Bob Dylan, and each line is a lyric from different Dylan songs arranged in a cento. This cento is a new transformative piece of work, follows a known formula that took skill and labor on the part of the poet, and gives credit to the original copyright owner. It might pass the first step.

Second, look at the significance of the copied content in the derivative work. It has to be enough that the original copyrighted material is still recognizable within it. If a line of music is placed within a poem such that the average reader doesn’t recognize the original song, then maybe it is not enough of a borrowing to bother with. For example, a line that uses the words, “like a rolling stone,” might not be recognizable as Bob Dylan’s without any other context or borrowed lyrics. Pair that with more Dylan in, “the answer is blowing in the wind like a rolling stone,” and a problem arises. The cento example in Step 1 might easily have failed this test if only because it relies on the recognition of Bob Dylan’s lyrics to make its effect.

…poets cannot rely on the assumption that because poetry doesn’t pay financially, it is always fair use to quote another poet, writer, or musician whose copyright has not passed into the public domain without getting the originator’s blessing.

And now, the third test asks what would be the impact of a poem using a line from a Dylan song printed in a poetry journal on the income or reputation of Bob Dylan. This test is only relevant if the poet’s fair use was taken in the entirety of all the steps. Dylan just sold his entire songwriting catalog to Universal for more than 300 million dollars. The financial/reputational impact of a single poem on a giant record label would be even more questionable than its potential to harm Bob Dylan’s reputation or the market for his work. I question, honestly, who would sue a poet for damages even if harm could be established.

While it wouldn’t seem worth the effort to sue a poet, I will add a fourth question for the simple poet contemplating great things for their poetry: what are their intentions for one day publishing this work? When a small journal obtains initial copyright to their single poem, they may not see any backlash from the original copyright owner, whom they borrow from. However, if their poem becomes part of a book manuscript, the publishing house is a bigger target for a copyright infringement lawsuit, and they might shy away from the controversy no matter how fair the poet’s use of the material is. It is the subjectivity of judge and/or jury that makes publishers skeptical about derivative works without permission.

On the one hand, poets cannot rely on the assumption that because poetry doesn’t pay financially, it is always fair use to quote another poet, writer, or musician whose copyright has not passed into the public domain without getting the originator’s blessing. On the other hand, poets must, in their creative process, trust that their transformation of another artist’s work has been stamped with their own originality. If poets pay tribute to those from whom they borrow for the sole purpose of creating new art, they can feel safe that their derivative works are fair use. Sadly, poets who want to be published are subject to the willingness of the publisher to defend a copyright infringement lawsuit. Robert Zimmerman is well known to have “borrowed”—though “geniuses steal”—from folk songs, musicals, and movies in both his music and lyrics (even taking his last name from Dylan Thomas). This is a poetic license all artists rely on—publishers be damned.

Cathy Wittmeye earned her JD from the University of Pittsburgh School of Law and her MFA in Poetry from Carlow University. She is a member of the Pennsylvania Bar Association since 2005. cathywittmeyer.com

The Stop Sign and Sex, Drugs and Alcohol in They Call Us, Issue #5, Winter 2021.

Crow Island Offering, The Page Gallery, Camden Maine, Poetry In Motion Exhibition October 21 – November 27, 2021 and read at The Poets Corner.

Curse Words, the tiny journal, issue iv 2021

Thrill-Seekers, Tangled Locks Journal, June 18, 2021

They Will Kill Us , Book of Matches, Issue 2, 2021 at pages 46-47

It Has No End, Funicular Magazine, March 4, 2021

A Night at the Paradise Motel, Somewhere, California and Wow, Plants and Poetry Journal, issue 6, January 2021

Raising Anchor, Seratonin Press, December 2020

knotted, a chapbook, was selected as a finalist in the 2020 Broken River Prize by Platypus Press

Paper Baby, appeared in Show Us Your Papers, a Poetry Anthology, Main Street Rag, October 2020

At Breakfast, When He Turned Twelve, My Son Asked About His Birth

The whole sky cracked

like a soft-boiled egg

smacked against the table

on a Sunday morning.

The puckering floor

crumpled and fell away

beneath my feet.

Seconds ticked

hours before time

stopped

silence surrounded

& I fell

sailing softly on air

& you were there

just like that

asking me to breathe again

such sweet molecules

my lungs never knew.

I gulped

a waterfall slowly,

savored atoms

that slid over my sandy tongue

& down my dusty throat

to circle around my tired heart

where yours beat a tympani

to my bass

& the space that held us

filled with symphonic percussion

awaiting the strings to strike their bows

at the moment your tiny nails pierced

my skin until my ears forgot both

the clash and the silence.

I sank into the darkness of your gaze

for a count the conductor lost too:

a quiet you and I will never

hear again.

Appeared in the Poet’s Choice anthology, For Expecting Mothers, 2020

Norderney Nerves

This poem appeared in The Esthetic Apostle, May 2019.

Norderney Nerves

Visit Norderney…sooner…for the storms that batter this island are constantly reshaping the landscape. – traveler.com

You should have brought a windbreaker, child – no, woman.

You smell the softness of iodine on the breeze that intensifies

cold sand on your soles until the breaking rays

blind and burn the glare of your porcelain shoulder

as fragile as the rainbow mussels’ shards piercing

such tender feet oblivious to their luminescence.

Low sweeps and mourning shrieks of gulls

draw your eye to a washed-up Tern stranded

on the basalt Buhne headless, and to a misty white

that disappears where the obsidian rolls choppy.

This is neap tide when pulls of celestial bodies

work against each other. Seagulls tossed

in reverse-glides upward, resign to new aims.

Sand, like blizzard ice, pelts skin, chafes.

Grass whips chaste flesh, smarting, drawing blood.

Inky black spills into the milky turmoil of white caps

like salt abrading our lips as we dash behind

saddened glass that pleads to come inside too

– knocking – pounding – whining.

An enveloping dome of charcoal-blue frames the deck flags

held back on poles like violent boyfriends they cannot escape

no matter how fast they run. And the bluster

abruptly stops with the warm return of Sun.

I brought you to the sea today to calm our nerves.

I failed to consider the island weather’s temperament.

Peeling Bark Floats Silver and Papery

If I write a poem about watching fire catch a log in my fireplace,

will you say the fire is not fire and the log is something else?

If I describe how flames tickled their way to the log’s dead heart,

will you tell me it is a desire to fill a void afraid to be named?

If I tell you the log is a volcano whose fire explodes from within,

will you call my metaphor repressed sexual energy or poetic anxiety?

If I describe peeling birch bark silver and papery floating out the flue,

will you tell me my consciousness of passing time has entered the poem?

If I tell you that smoke is churning out a crevice and spinning like Dorothy Hamill,

will you say time is of the essence, so write, write, write, and stop complaining?

If I write the kindling turned to coals that would fill a Florida sunset with envy,

will you tell me to stop being jealous of other poets and find my own voice?

And if I tell you when I stoked this fire, it roared in my face,

will you say I should turn my questions into statements?

I just sat down to look at the fire, but a fire always has an opinion.

Work to Do

“Work to Do” first appeared in issue 2.54 of Noble Gas Quarterly, December 2018. This is a revised version.

I like to think he was swimming in pure amniotic fluid

—save the champagne that first night.

I kept his space pristine: no wine, no lattes, no 2nd-hand smoke.

I like to think of him on our first escape to the sea – the Priel –

his toddled footprints in foamy morning sand where, in the shallows,

I blew in his face, so he held his breath, submerged and swam.

I like to think I leave him swimming in the purest atoms of H and O

breathing air that is trusted breath absent soot and acidic mist.

Instead, I leave him the task of cleansing it

without the tools to do it.

I leave him beaches awash in medical waste

& honeybees choking on pesticides

I leave him molten roads in scorching heat

I leave him flames performing seed serotiny

I leave him instead, with work to do.

Possession, selected for an honorable mention in the Difficult Fruit Poetry Prize by IthacaLit Poetry in 2018

Readings

Cathy was featured on the Viewless Wings Poetry Podcast April episode, reading her poem, “Succulent”

Click to listen

Workshops and Presentations

Negotiation is a Life Practice: a talk with MBA students at University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain, 9 February 2024